The Architect and the Concept

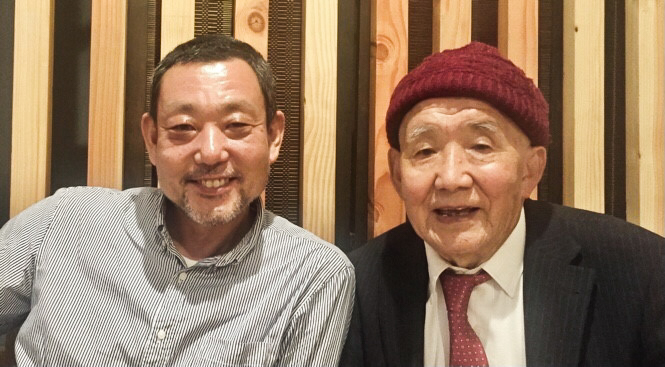

Yasuda Kenji / 安田憲二

YASUDA Kenji was born in Osaka, Japan and studied architecture at Kobe University, followed by a master’s degree in Engineering. After working at several architectural design offices, he set up his own firm in Osaka in 1999.

Yasuda is keenly interested in environmental planning, and nature is his guiding force when designing buildings as pleasant living spaces in harmony with their environment. He likes to invite external environmental elements such as sunlight and wind into the building space, and the interfaces between men and materials, and between men and men is of prime importance.

Yasuda’s interest in Indian architectural design led him to travel to India for 2 months at age 30, exploring both temple architecture and city design in Ahmadabad, Ladakh, Jaipur, etc., each featuring a unique architectural beauty, reflecting features such as natural weather, culture, and varying ethnicity. He was also keen to visit Chandigarh, a city designed by one of the fathers of contemporary architecture, Le Corbusier.

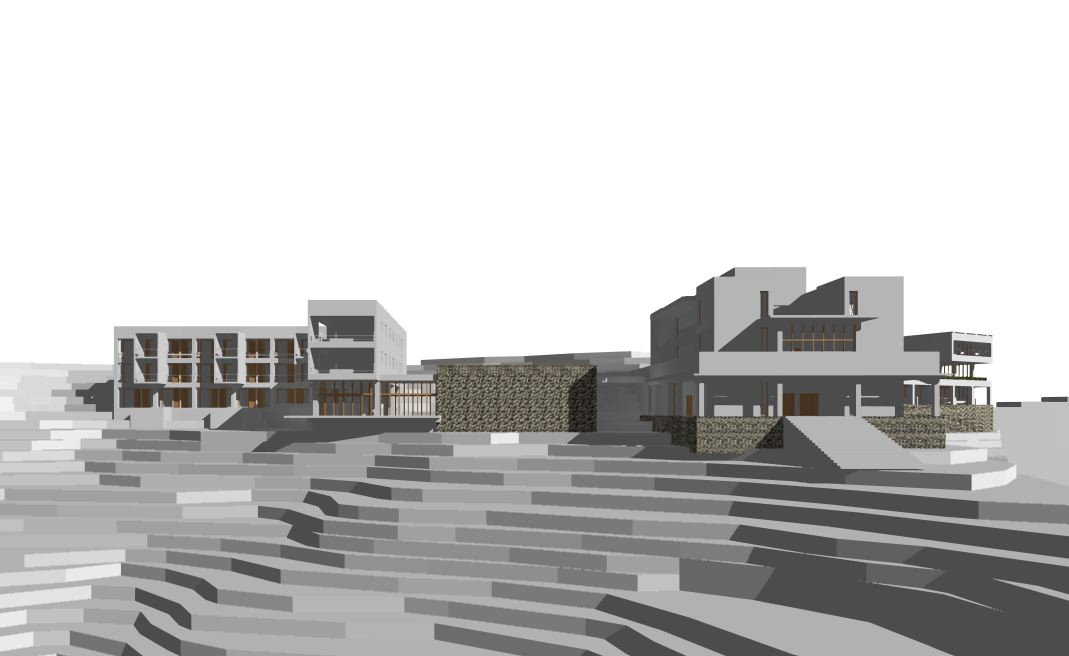

Yasuda drew on these experiences when working on the overall design of Pelri Thegchog Ling/Buddha Pāda Institute, a creative living space that is rich, rooted, natural and welcoming.

Yasuda’s Design Concept

For example, a traditional Japanese house will often have sliding glass doors extending the width of the house. In this way, those residing there have unbroken visual connection and immediate access to the garden outside. This sense of connected space perception pervades all of Yasuda’s building plans.

Yasuda begins to create a new design without any specific idea or concept. It is like remaining in Buddhist emptiness and allowing the plan to arise in contemplation while just visualizing or visiting the environment of the planned construction site. In this way, he absorbs the conditions of the natural environment, shape of the land, terrain, etc. In a sense, this could be considered a Japanese approach to design — not attempting to dominate or overcome the environment, but rather to find harmony with the circumstances.

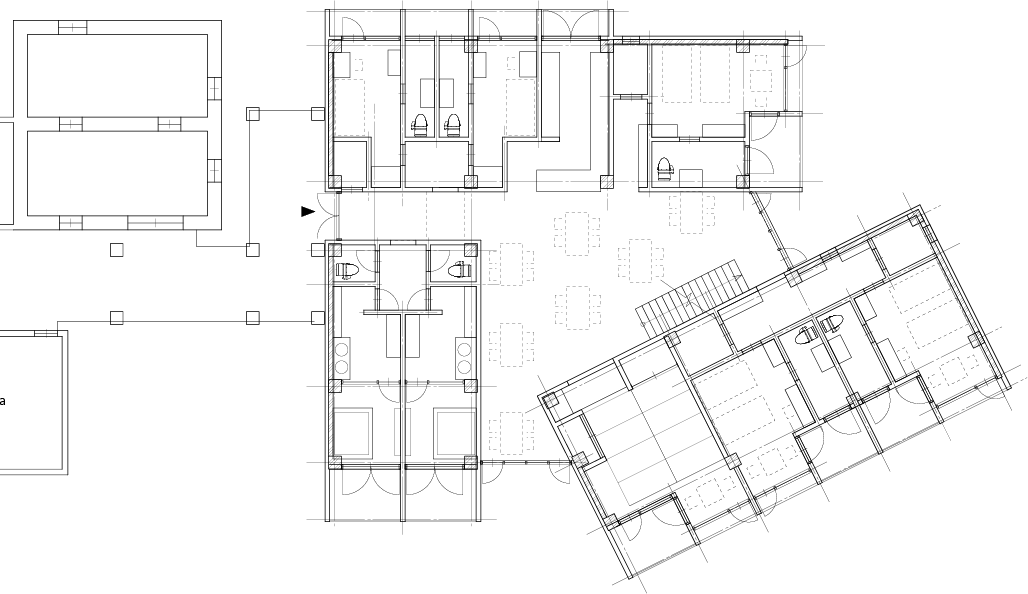

For example, Bashō House, our guest facility, has an atrium in the center with the rooms and bathroom arrayed around this empty space. This space gives a feeling of freedom, encouraging a relaxed and friendly atmosphere.

Construction Materials

Yasuda also prefers that the buildings not look brand new, but rather as though they have been weathered in the Kalimpong climate for a long time. Thus, we haven’t strived to make things exceptionally beautiful, but rather aimed to keep appearances as natural as possible.

This is a manifestation of the Japanese wabi-sabi ideal in Japan. We find beauty not only in newness, but also the weathering and natural impermanence of things over time.

Appropriation of Local Design Features

These beautiful and varied stones were then used to decorate the walls.

How the Construction Proceeded

Years of working with the local carpenters and other craftsmen familiarized them with our requirements, easing the process greatly.

Basic Design Process

1) Following the Footsteps of the Buddha — Learning in Nature.

The climates of Kalimpong and Japan are very similar, and it seemed that feeling of seamless connection between inside and out could be expressed in concrete instead of wood as in Japan. The buildings were arranged to be integrated with nature as comfortably as possible. In addition, although situated on sloping land, the design minimizes height difference between the buildings so people can move between buildings with ease.

2) Ecological Considerations

3) Health Considerations

As writer, philosopher Alain de Boton puts it, “Beauty is a likely outcome whenever architects skilfully mediate between any number of oppositions, including the old and the new, the natural and the man-made, the luxurious and the modest, and the masculine and the feminine. Buddha Pāda Institute and Bashō House are superb examples of this beauty.